Topics > Tyne and Wear > Newcastle upon Tyne > Newcastle, 1855 > Newcastle History

Newcastle History

Extract from: History, Topography, and Directory of Northumberland...Whellan, William, & Co, 1855.

It is now agreed by antiquarians, that Newcastle occupies the site of the Roman station Pons Aelius, but of its history during the time this country was under the imperial dominion, nothing is known with any degree of certainty. Subsequent to the withdrawal of the Roman legions, and during the Saxon period, the town was known by the name of Monkchester, which originated in the number of religious. establishments that were situated in the town and neighbourhood. Previous to the Danish invasions, religious institutions of various kinds flourished here, but, from the time of Alfred to the Conquest, the Northmen carried fire and sword whithersoever they went, and at the commencement of the Norman period, religious establishments of every kind had almost totally disappeared from Northumbria.

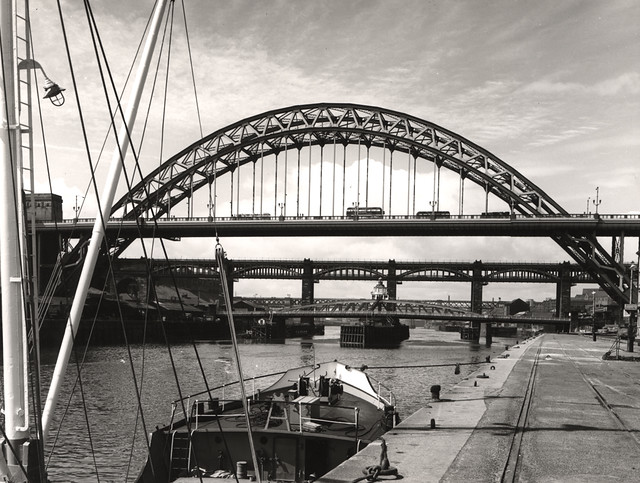

The Conqueror had scarcely established himself in his newly acquired dominions, before Monkchester experienced his severity. Malcolm, King of Scotland, and Edgar the Etheling, having invaded England, were met and totally defeated by William on Gateshead Fell, and in order that they might not find an asylum in the town, he caused Monkchester to be almost entirely demolished. It was not long before Malcolm was again in arms and renewing his ravages in Northumberland. The Conqueror sent Robert, his eldest son, to chastise the perfidy of the Scot, but the two princes did not meet, and the only result of the expedition was the erection of a fortress at Monkchester, which henceforth bore the name of Newcastle, As this stronghold protected the passage of the Tyne at this point, it has always been a place of great importance, and on the completion of the castle and fortifications the town rapidly increased in size and population, receiving many immunities from William and his successors. So early as the reign of Rufus, it was completely enclosed with a wall and fosse, and endowed with all the privileges of a free borough.

As the castle was erected by one son of the Conqueror, it is a singular circumstance, that another son was the first to employ force against it. In 1095, it was seized by the adherents of Robert Mowbray, Earl of Northumberland, and did not surrender to Rufus until after a short siege, when several of the Earl's followers fell into the hands of the monarch. The Earl being driven from Tynemouth by the King, took refuge in his castle of Bambrough, from whose walls he continued to defy the arms of his sovereign. An insidious offer to betray Newcastle into his hands induced him to quit Bambrough, in the dead of the night with no more than thirty horsemen. In advancing towards the town he was discovered and pursued to Tynemouth, where he was captured in the Church of St. Oswin. Bambrough afterwards surrendered, and the Earl was removed to Windsor Castle, where he died after thirty years imprisonment.

Nothing of any importance transpired in Newcastle till the reign of Stephen, when we find it occupied by David, the Scottish King, who had hurried across the borders, reduced Carlisle, Norham, Alnwick, and Newcastle, and, made war upon Stephen in support of the Empress Matilda, his niece, by whose desire a treaty of peace was concluded in 1139. By the terms of this treaty it was agreed that the town should remain in the hands of the Scots, who held it for sixteen years, after which period it was restored to the English crown.

William the Lion, King of Scotland, having joined the league against Henry II., burst into England in 1174, bringing ruin and desolation wherever he appeared, but while tilting in careless security in the neighbourhood of Alnwick, he was surprised and made prisoner, with many of his principal barons. He was afterwards ransomed, and on his return to Scotland, a serious conflict took place on Tyne Bridge between the inhabitants of Newcastle and the royal attendants. Enraged at seeing their old enemy once more at liberty, the people attacked the royal cortege, and William was obliged to cut his way through the exasperated masses by which he was surrounded. Sir John Perth and others of the royal escort were slain in the affray. Newcastle was several times visited by King John, who seems to have had a great predilection for the old town. He repaired and strengthened the fortifications of the castle, and instituted a Society of Free Merchants, the members of which were exempted by him from pleading anywhere beyond the walls of the town to any plea save that of foreign tenures he also released them from the duties of toll, lastage, pontage, and passage, in all the sea-ports of his dominions both at home and abroad, empowering the Mayor of Newcastle, or Sheriff of Northumberland, to give them reparation for any injury they might sustain. The succeeding sovereigns, Henry Ill., Edward II., and Edward Ill., confirmed this charter and added to it new privileges. In 1235, Henry Ill. granted a special charter to the men of this town, by which all Jews were prohibited from residing in it, and in 1238, be gave the townsmen the lands called "the Forth and the Castle Field," with permission to dig coals there. About this period. Newcastle suffered severely from pestilence and famine, to which great numbers of the inhabitants fell victims.

ln consequence of a dispute about the possession of the northern counties, Alexander of Scotland, and Henry III. of England, met in Newcastle, where a conference was held in 1236. The dispute not having been settled, the English army assembled here in 1244, but hostilities were prevented by the mediation of the Archbishop of York. Shortly afterwards the town suffered severely from fire, the greater portion of the buildings, and the bridge over the Tyne, being destroyed by the conflagration. We find Edward I. here in 1396, when, in consequence of the manner in which Englishmen had been treated at the Scottish court, Edward summoned Baliol to meet him at Newcastle, on the 1st of March, on which day the English King arrived, accompanied by an army of 30,000 foot and 4,000 horse. Having waited some time for Baliol's appearance; Edward advanced with his army to Bambrough, where he also delayed and repeated his summons. The destruction of a Scottish detachment, in an attempt to surprise the Castle of Wark, was the signal for war. While the town of Berwick was stormed by the English, Corbridge and Hexham were destroyed by the Scots. Edward, however, was not to be deterred from his plan, but pushing forward the war with vigour, in the short period of two months, captured all the principal strongholds in Scotland. This was followed by the submission of Baliol, who did homage to the King of England at Berwick. The following year, Wallace, the Scottish leader, entered Northumberland, ravaging and laying waste the country to the very walls of Newcastle, but when he came near the town, finding that the inhabitants had made all necessary preparations for its defence, he changed his route and shortly afterwards returned to Scotland. After the death of Wallace, the cause of Scottish independence was espoused by Bruce, who defeated the English in several encounters. Edward, being determined to reduce the Scots to obedience, collected a large army at Newcastle, and advanced into Scotland, where he was totally defeated at the Battle of Bannockburn.

Subsequent to the events above narrated, the inhabitants of Newcastle suffered severely from famine and pestilence, and their misery was so great that they were compelled to eat horses and dogs. The old historians inform us that for very hunger the thieves in the prisons devoured the new comers, nay, even that parents did eat their own children." These horrors were increased by an invasion of the Scots, who were so numerous in Newcastle that, it is said, “they wist not where to lodge.''

Immediately after the accession of Edward III., the dissatisfaction of some English barons, who had been deprived of their lands in Scotland, kindled a new war between the two countries. After various successes the Scots were completely overthrown at the battle of Halidon Hill, and the Scottish monarch performed homage for his crown and kingdom, in the Dominican Church, at Newcastle, binding himself by oath to hold his kingdom of the King of England, for himself and successors for ever, transferring at the same time to the English monarch the five Scottish counties bordering upon England, to be annexed to that crown for ever. This state of things did not long continue, for, the French king being defeated at Cressy, lost no time in urging David of Scotland to invade England. The Scottish monarch assembled thirty-three thousand horse, and, intending to create a diversion in favour of the King of France, entered England. Passing by Hexham, he vigorously, but vainly, attempted to take Newcastle by storm, and marching into Durham laid the whole county waste. Thinking that the country was utterly defenceless, he talked of nothing less than marching to London, but the bishops and lay barons of the north had collected a small but resolute band, and went in quest of the invader. The skill of the English archers prevailed over iron panoply, the men at arms charged the Scottish host, and the infantry completed the rout. Fifteen thousand Scots lay dead, and David himself, with the flower of his nobility, remained in the hands of the conquerors. The broken shaft of Nevill's Cross still marks the scene of carnage. After the battle of Poitiers the Scots ransomed their king, and concluded a peace for five and twenty years. Henry IV., having ascended the throne, upon the deposition and murder of the unfortunate Richard II., granted to Newcastle a charter, by which the town and its suburbs were separated from the county of Northumberland and made into a county of itself, under the title of the county of Newcastle.

Among the great days of this ancient town was that on which, in 1503, the Princess Margaret, daughter of Henry VII., passed through Newcastle, on her way to Scotland, where she was to become the bride of James IV. Leland, who gives a detailed description of the journey of the princess, tells us, that Margaret and her splendid retinue were met about three miles from Newcastle, by the Prior of Tynemouth and Sir Ralph Harbottle, the former attended by thirty, and the latter by forty, richly attired horsemen. Upon entering the bridge the procession was joined by the Earl of Northumberland and his retinue, the collegiates, the carmelite friars, the mayor, the sheriff, and the aldermen, clad in their several modes. Then, as old Leland tells us, "at the bryge end, upon the gatt, was many children, revested of surpeliz, synggyng mellodiously hympnes, and playing on instruments of many sortes." Within the town, all the houses of the burgesses were decorated, and the streets, house-tops, and rigging of the shipping, were filled with spectators, including "gentylmen and gentylwomen in so grett number that it was a playsur for to see."

The annals of Newcastle in past ages are chiefly filled up with accounts of wranglings and fightings between the English and Scotch in times of enmity, processions and feastings in times of peace, and terrible visitations of the plague, which seem to have been more frequent here than in almost any other town in the kingdom. In 1603, King James spent four days here, on his way to London, to become crowned King of England. He was received at the gates of the town by the mayor, aldermen, and councillors, who presented the burghal keys and sword, together with a purse of gold, to his majesty, who graciously returned the former, and as graciously, retained the latter. On the Sunday, the king attended divine service at the church, where the Bishop of Durham preached before him, and on the Monday he visited the whole of the town, releasing all prisoners, "except for treason, murther, and papistrie." The townsmen of Newcastle were so elated at the royal visit, that "they thankfully bare all the charges of the king's household during the time of his abode with them," and, if we are to believe history, James must have been anything but displeased to let his new subjects take this honour to themselves. On the occasion of a temporary visit to Scotland, fourteen years after, James again visited Newcastle, and again was he presented with a purse of gold by the municipality.

We find Newcastle much involved in the turmoils of the civil war, and there seems to have been a strange mixture of loyalty and republicanism afloat at that period in the town and neighbourhood, for Charles I., in 1646, having fled from his enemies in the midland and southern counties, took refuge at Newcastle, and placed himself under the protection of the Scottish army, by whom he was kept in a sort of honourable confinement. Bourne tells us, "that upon his majesty's entrance into Newcastle, he was caressed with bonfires and ringing of bells, drums and trumpets, and peals of ordnance, but guarded by 300 of the Scottish horse, those near him bareheaded." We are also further informed, "that the king and his train had liberty every day to go and play golf, in the Shield-field, without the walls." The people, on one occasion, took a singular mode of showing their sympathy for him. "A little while after the king's coming to Newcastle," says Whitelock, "a Scotch minister preached boldly before him, and, when his sermon was done, called for the fifty-second Psalm, which begins :-

'Why dost thou, tyrant, boast thyself,

Thy wicked works to praise ?’

Whereupon his Majesty stood up, and called for the fifty-sixth Psalm, which begins :-

'Have mercy, Lord, on me, I pray,

For men would me devour!'

The people waived the minister's Psalm, and sang that which the king had called for."

Charles, however, was imprudent enough to attempt an escape from New·· castle under circumstances which presented very little prospect of success, and a consequence of his failure was, that the remainder of his residence in that town was rendered more irksome. The troops, Bourne tells us, discomforted the fallen monarch: "The king, having an antipathy against tobacco, was much disturbed by their bold and continual smoking in his presence." At length, in the next following year, the Scots gave Charles up to the English, and the unfortunate monarch was marched off to London. The historical proceedings of Newcastle, after the termination of the civil war, settled down into mere annals, disturbed only in two instances the rebellions of 1715 and 1745 on both which occasions Newcastle appeared among the defenders of the Hanoverian line.

In December, 1831, the cholera commenced its ravages in Newcastle and Gateshead, from which time, up to March, 1832, it had carried away 544 persons. The two towns were again visited by this dreadful scourge in 1849, and in 1853 they experienced a third visitation, when 1,920 persons became its victims.

Also in this Directory (Whellan, 1855) for Newcastle:

- Description of Newcastle

- Early history

- Fire of Newcastle & Gateshead (1854)

- Extinct Monastic Edifices

- Fortifications, etc.

- Churches and Chapels

- Public schools

- Hospitals and Almshouses

- Benevolent Societies and Institutions

- Public Civil Buildings, etc.

- Literary and Scientific Societies, etc

- Commerce and Manufacturers, etc.

- Corporation, etc.

- General Charitities of Newcastle-upon-Tyne

- Eminent Men

- Post Office, Newcastle

- Directory of Newcastle-upon-Tyne