Topics > Tyne and Wear > Newcastle upon Tyne > Newcastle, 1855 > Commerce and Manufacturers in Newcastle, 1855

Commerce and Manufacturers in Newcastle, 1855

Extract from: History, Topography, and Directory of Northumberland...Whellan, William, & Co, 1855.

COMMERCE AND MANUFACTURES, etc.

In viewing the vast industrial features of Newcastle, the absence of unity of object in its various manufactures never fails to attract the observation of the stranger. "It is not,'' says a popular writer, "as at Manchester, where cotton reigns supreme; or in the West Riding towns, where wool is the staple of industry; -or at Sheffield, where steel is the be-all and do-all; or at Birmingham, where everything imaginable is made from every imaginable metal; or at the Staffordshire Potteries, where every one looks, and works, and thinks, and lives upon clay; or at Leicester, where stockings are regarded as the primum mobile of society. It is not thus on the Tyne; for though the collieries are beyond all others the characteristic features of the spot, yet their works are mainly subterranean : they seem to belong to a nether world, whose fruits appear at the surface only to be shipped and railed away to other regions. But we may probably find that this rich supply of coal has been the main agent in inducing the settlement of manufacturers on the Tyne, for most of the large establishments are of a character which render a great consumption of coal indispensable.”

In treating of the various manufactories we will place the engineering establishments in the first rank. Establishments of which Newcastle may be justly proud, not from their antiquity, but from their connexion with the name of Stephenson. This town is in every respect, the birth place of locomotives, and some of the largest and finest steam-engines in the world are erected here. No where could a mora fitting place be found for this wonderful manufacture, than the home of the extraordinary men who, beyond all others, have been mainly instrumental in developing the railway system.

Near the spot where the viaduct crosses the Close to reach the Castle Hill, the works of Stephenson are situated. There are the open yards, surrounded by buildings, the forging and casting shops, where the rougher portions of metal are prepared; the filing and planing shops, in which the surfaces are smoothed and polished; and the fitting shops, where all these elements are brought together in proper relations. The materials are iron, copper, brass, steel, and a. little wood forging, casting, rolling, drawing, boring, turning, planing, drilling, cutting, filing, polishing, rivetting, these are the processes, from and by the aid of which the mighty engine is constructed, which, according to the opinion of some, Southey foresaw when he described " The Car of Miracle'' which

"Moved along

Instinct with motion ; by what wondrous skill

Compact, no human tongue could tell,

Nor human wit devise.

Steady and swift the self-moved chariot went."

Locomotives in every stage of progress meet the eyes on every side. Here is one of these iron monsters without its chimney, another without its fire box another has a man inside it hammering away with all his might, another is having the pistons put in, to another side plates are being screwed on, another is being set on its legs wheels we should say, another is being painted, and there, a crane has taken up another in its strong embrace, drawing it bodily upwards on to a strong carriage, and it is ready to start off to perform its civilising, space annihilating work in the busy world outside. A locomotive of the present time is both a manufacturing and a commercial study. When we reflect that such a machine, contains more than 5,000 separate pieces of metal, and that its general price is about 2,000 guineas, and that one single railway company possesses more than 600 such machines, can we fail to observe the vast amount of manufacturing and commercial energy developed in this direction?

The following epitome of the life of the late George Stephenson, may not be, deemed out of place in this part of our work. He tells us that he was a colliery boy in early life, and how as time rolled on, he became the breaksman of Killingworth Colliery, at which time he commenced his education, and during the "night shifts" often employed his time in repairing the pitmen's clocks and watches for small charges. Speaking of this period of his life, he says, “I have worked my way - but I have worked as hard as any man in the world, and I have overcome obstacles which it falls to the lot of few men to encounter. I have known the day, when my son was a child, that after my daily labour was at an end, I have gone home to my single room and cleaned clocks and watches, in order that I might be able to put my child to school. I had felt myself too acutely the loss of education, not to be sensible of how much advantage one would be to him.'' By degrees he contrived to make improvements in some of the engines, and this becoming noised abroad, he soon had work enough to do. What with putting up steam-engines under-ground and mending those above-ground-what with laying down tramways, and mending horse-gins, and doctoring boilers for steam-engines. Geordie, (as he was called at that time) was on the tramway to fortune, and gave up mending watches, making shoes, cutting clothes; and all his old practices, except that of brightening up little Bobby, who was now become a thriving “cute lad." He subsequently applied his mind to railways, and his engine, the ''Rocket," gained the prize of £500 on the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. In proportion aa railways and locomotives increased so did his gains and fame - and, finally, the poor pitman of Killingworth, who thought his fortune was made when his wages were advanced to twelve shillings per week, became possessed of a handsome fortune and estate, and saw his son Robert becoming a great and wealthy man before he died, in August, 1848. Speaking of himself, he said, “I may say, without being deemed egotistical, that I have mixed with a greater variety of society than perhaps any other man living. I have dined in mines, for I was once a miner, and I have dined with kings and queens, and with all grades of the nobility, and have seen enough to inspire me with the hope, that my exertions have not been without their beneficial results - that my execrations have not been in vain.” Such was George Stephenson, the trapper, breaksman, engineer, pump-doctor, locomotive engine manufacturer, and rail- way engineer of the first railways, and the father of that son whose name is, and will be, famous wherever railways are known.

The next great feature of the Tyne industry is the manufacture of glass, which is made in immense quantities in and round Newcastle - not merely in one of its forms, but in every variety of plate-glass, sheet-glass, window-glass, flint-glass, and bottle-glass. We are informed by Bourne, that this branch of industry was established on the banks of the Tyne in the reign of Elizabeth but, certain it is, that it was in full operation at the commencement of the 17th century, and Grey, writing in 1649, makes mention of "the glass-houses at the Ewes Burne, where plaine glasse for windows ill made, which serveth most parts of the kingdom." We must look for the settlement of this important branch of trade in this neighbourhood to the cheapness and abundance of coal, alkali, and sand, and to the fact of the vicinity of shipping ready to carry the manufactured produce to every part of the globe. Let us, therefore pay a visit to one of the establishments where glass is made, that we may acquire some knowledge of its manufacture. Speaking of the manufacture of plate glass, Mr. George Dodd says, "We see the ingredients melting in the clay vessels in the fiercely heated furnace - the transference of this melted material to the cuvette, or iron bucket, the wheeling of the cuvette out of the fiery furnace on a miniature railway - the tilting of the cuvette, so that it shall pour out its golden stream of molten glass on the level surface of the cast-iron casting-table - and the cooling of this stratum into a sheet of solid glass, half-an-inch in thickness. We see this plate annealed in a carefully but not highly heated oven; and then we follow it through the processes whereby, by the aid of wet sand, ground flint, and emery powder, it is ground and polished to the form of that most beautiful of all manufactured substances ,a speckless, spotless, colourless, perfectly transparent sheet of plate glass. Or take the sheet-glass department. Here we see the workman, when the ingredients are commingled and melted, dip a tube into the melted glass ; roll the glowing ductile mass on a smooth surface ; blow through the tube, to make the mass hollow within ; swing the tube and the glass to and fro like a pendulum, until the hollow mass assumes the shape of a cylinder, and open the cylinder into a large flat sheet of glass, by a most extraordinary train of manipulations. Or let common crown or window-glass be the object of our attention. Here we see the ingredients - chiefly sand alkali, and lime - melted in the furnace; and the striking mode in which the workmen, after gathering eight -or ten pounds of viscid glass on the end of a tube, blows and whirls and whirls and blows again, until the hollowed mass of glass suddenly flashes out into the form of a flat circular sheet. Or let it be flint-glass, where after a mass of the semi-liquid material has been blown hollow on the end of a tube, and is brought, by a few simple tools, to the form of a goblet, decanter, wine-glass, or other vessel, in a way that almost baffles the eye and the comprehension of the most attentive observer. Or, lastly, if bottle-glass be the form in which the material is produced, we see the mode in which the employment of cast iron moulds is made to bear its share in the general routine of operations."

Previous to the repeal of the glass duty in 1845, 14 companies were engaged in this branch of industry, during the years 1846 and 1847 the number of companies was increased to 24, at present there are only 10. During the last year of the duty (1844), the 14 companies then in existence, made 670 tons of crown and sheet glass, for which they paid £500,000 duty. The 10 companies now working, produce 35,500,000 feet annually, equal to 15,000 tons, value £225,000, being an increase of considerably more than cent per cent, and at a charge to the public of less than one half the former duty. In polished plate there are six companies, being the same as existed in 1837, their number has remained stationary but their production is estimated to have doubled. They now make 3,000,000 feet of polished plate glass annually, equal to 5,500 tons, valued at £450,000. The produce by the little kingdom of Belgium, the greatest glass producing country in the world, is 50,000,000 feet of sheet glass annually, equal to 22,300 tons, or 25 per cent, more than is made in England, of both crown and sheet glass. They export of this quantity 85 per cent, of which 6 per cent comes to England, and they retain 15 per cent, for home consumption. England retains 85 per cent, of its produce for home consumption, and exports 15 per cent, being about double what she imports.

The Chemical Works of the Tyne, though of comparatively modern introduction, hold a distinguished position among the manufactories of the north. We find them on both sides of the river stretching from Newcastle to Tynemouth, and we may form some notion of the extent and variety of the marvellous transmutations which are taking place within them, from the number of lofty chimneys whose summits are observable in every direction. These establishments produce soda, potash, sulphuric, muriatic, and nitric acids; chlorine, chloride of lime, alum, red-lead, etc., in great quantities. Some of these establishments are beautiful examples of scientific system, and present many striking features. In the preparation of sulphuric acid, for instance, there are in one establishment, leaden chambers employed, each two hundred feet in length, twenty in breadth, and twenty in height - these are to contain the sulphur-vapour, from which the acid is afterwards formed. The same establishment possesses a platinum crucible, or still, in which acids are boiled, which cost as many guineas as it weighs ounces - one thousand!

The lead works, again, are notable features. The lead produced by the rich mines of Alston Moor, and the dales of the Allen and the Wear, is smelted in “pigs," or oblong blocks, in which condition it is brought to Newcastle, and here it is exposed to the operations of refining, shot-making, red-lead making, and white-lead making, or it is transformed into various forms of pipes, sheets, etc. Nearly all lead contains a little silver; if the proportion be even so small as five ounces of silver to a ton of lead, it will repay the process of refining, and this refining is a delicate and beautiful process, in which the silver by its different mechanical and chemical properties, is separated, little by little from the lead. We find lead refining in this district mentioned so early as 1699. One of the principal sources of the celebrated Roger Thornton's wealth was the lead mines which he possessed in Weardale. This surmise is corroborated by the vast quantities of lead which he bequeathed to the various churches, monasteries, and other religious establishments in Durham and Northumberland. Shot-making was carried on in the Manor Chare in 1749, and the shot tower and lead works at Low Elswick were established in 1796. This curious process is well worth observing. We see how the melted lead is dropped through the holes of a kind of colander how it falls into water at the bottom of a pit, perhaps a deserted coal-pit, one or two hundred feet in depth - how it here solidifies into small roundish drops - how these drops are first dried, and then sifted into different sizes how the well formed shot are separated from the badly formed and how they are finely churned in a barrel, with a little black-lead, to give them a polish.

Potteries are also numerous in this busy place. Earthenware was produced here as early as 1623, and in 1791 we find seven potteries in full operation. The potteries of the Tyne do not aim at the dainty and tasteful, they are content with the useful their pots have to bear rough usage, and they are made roughly. There is abundance of clay in the vicinity of the Tyne and the Wear, fitted to make the coarser description of pottery, and this circumstance, coupled with the abundance of coal and of shipping, enables the northern district to drive Staffordshire out of the market in supplying coarse goods to Germany, Denmark, and other northern countries.

To enter into a description of all the branches of industry pursued in the vicinity would indeed be a Herculean task, we will only add that, besides the manufactories just mentioned, there are oil mills, where oil is obtained, by pressure, from linseed, hempseed, and rapeseed, - turpentine works, where the rough substances, black and yellow resin, and the transparent oil of turpentine, are obtained by the distillation of the viscid turpentine which exudes from fir trees, - starch works, where starch is obtained from flour, - also soap works, - sail-cloth factories, linen-yarn factories, and paper-mills. AlI require furnaces for carrying on operations, and the abundant supply of coal in this district furnishes, as we have before remarked, a strong inducement to this localisation. Thus far have we sketched the trade of Newcastle, and although, no doubt, it is indebted to its position for much of its celebrity, yet we must principally attribute the proud station which it now occupies as a seat of commerce and manufactures, to the energetic exertions and enterprising spirit of its population, the products of whose industry are bartered for palm oil and ivory on the coast of Africa, are exchanged for tea in the ports of Hong Kong, for tallow and timber in the ports of the Baltic, for grain on the shores of the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, and for hides and dye-wood, and coffee and sugar and the other products of the tropical regions, on the east and west coasts of America. By day is heard the piping whistle of the steam engine and the whirring of machinery - by night thousands of fires spread their red and lurid glare, through the coal-field district, lengthening so to say, the day, which passes too quickly for the restless energies of the modern Northumbrians.

COMMERCE. The principal exports of Newcastle are coals ; lead, in its various forms and preparations ; glass, in its different varieties ; iron; in its various forms and conditions; earthenware, bricks, fire-bricks, painters' colours, chemical preparations, soap, linen and linen-yarn, sailcloth, woollen goods, leather, ropes, machinery, coal-tar, and grindstones. The trade in most of these articles, particularly in chemicals and the various preparations of lead, has been rapidly increasing for some time. The foreign import trade, in consequence of the most valuable articles of foreign produce being received coastwise and by rail from Hull, London, and other places, deals almost entirely in bulky articles for consumption in the town, and a limited circumjacent district. Its chief articles are grain, timber, hides, hemp, flax, tallow, sulphur, bones, oak-bark, Dutch cheese, wines, spirits, seeds, and fruits. The trade is much inferior to that of foreign exports, but it is rapidly increasing. In addition to the foreign and import, Newcastle possesses an extensive coasting trade, which consists chiefly in coals, and, next to them, in the same articles as those of foreign export. The principal additional articles are plate-glass, paper, bacon and butter, anchors and chain cables; and locomotive engines. The quantity and value of these goods are very large, and regular vessels are employed for their conveyance to London, Liverpool, Glasgow, Bristol, Hull, Dundee, Stockton, Yarmouth, and various Irish ports.

THE COAL TRADE. The period at which the Newcastle coal was first worked is not known with any degree of certainty, but we find it first noticed in record by the charter of Henry III, in 1245, which granted permission to mine it, It seems to have been known in the fourteenth century, not only in London, but also in France, though it did not become an article of commerce till the latter part of the sixteenth century. About the commencement of the following century, the French are represented as trading to Newcastle for coal, in fleets of fifty sail at a time, serving the ports of Picardy, Normandy, Bretagne, etc., even so far south as Rochelle. and Boudreaux, while other fleets, sailing to the ports of Bremen, Holland, and Zealand, supplied the inhabitants of the Low Countries. In the reign of Charles I., there was a great demand for coal in the metropolis, and we find from the official report of the Trinity House, Newcastle, that the exports for 1703 amounted to 48,000 Newcastle chaldrons. Vessels do not enter or clear at North and South Shields for the Tyne trade, but at Newcastle, of which those are the out-stations. The number of ships registered at Newcastle was, some years ago, 1,100, and their tonnage amounted to 221,276 tons. A collier makes, on an average, nine or ten (and sometimes more) voyages to London in a year, and the arrivals in the Tyne annually are not less than 13,000 or 14,000; 10,000 of which are on account of the coal trade. A very fine marine picture may sometimes be witnessed from a bold promontory on the coast. If you take your station on Tynemouth Priory, a well-known ruin, placed upon a rock jutting into the sea, when the wind has changed after long-continued easterly gales, you may see many hundred vessels, mostly colliers, put to sea together, rejoicing at their freedom after having been long wind-bound. On one occasion, some three hundred vessels, all laden with coal, were observed making sail together in a single tide, and distributing themselves over the ocean, with their prows turned in almost ever direction. Some were sailing southward and coastwise for English ports, for the Channel, and for the southern countries of Europe ; others were pointing northward, for Scotland and the Norwegian coast; others steered due east, for Denmark and the Baltic; and all were sinking deep in the water, weighed down by that mineral fuel which does more for our national advantage than auriferous sands and Peruvian or Mexican silver mines. These dingy and crawling craft are, or were, the "nursery of the British seamen,” for being constantly at sea, winter and summer, they necessarily train up a race of hardy and practised mariners. But then naval nursery stands, or floats on danger of abolition. A new line of dipper screw steamers have been started, and have at once reduced the time and cost of transit. These, again, have to contend with serious rivals the railways, which convey coal at one farthing a ton per mile, free from vexatious dues and duties, privileges and monopolies, all of which hang over the vessels like birds of evil omen. At least, let one collier brig be preserved as a specimen of things that were, it may soon be a mere curiosity. The first steam collier entered the Thames in September, 1852, having run the distance from Newcastle in forty-eight hours. She consumed eight tons of coal on the voyage, and brought 600 tons as cargo, the whole of which was discharged in the day, and the vessel went back for a further supply. The English coal is now sent to Vienna, and can be sold there cheaper than the Austrian coal, besides being far superior.

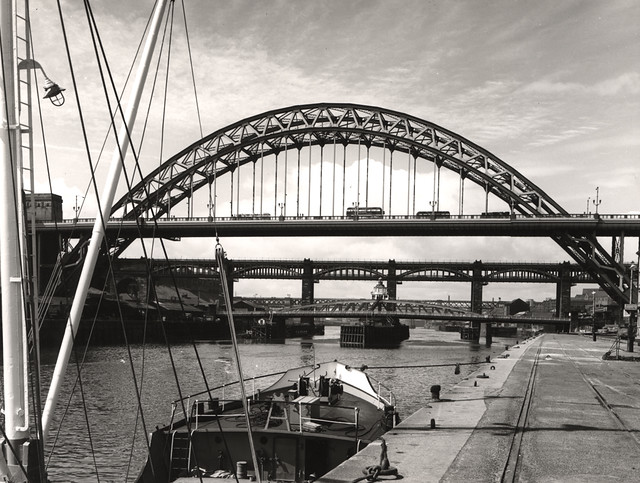

HARBOUR. We find that soon after the conquest records and charters were agreed upon, by which the width of the Tyne, near and below Newcastle, was divided into three parts, one of which was assigned to the county of Northumberland, one to the bishopric of Durham, and the middle of this channel was to be free to all. This division of the river led to many contests for the ownership and government of this important stream, but the general course of modern legislation has been to give increased power to the Corporation of Newcastle, whose jurisdiction formerly extended to high water mark on, both sides of the river, from the sea to some distance above Newcastle, including the creeks of Seaton Sluice and Blyth, and consequently the trade and shipping of Gateshead, North and South Shields, Blyth, and Hartley. This. jurisdiction was somewhat curtailed about five years ago, when Shields was created a distinct port. The Tyne, at Newcastle, has a mean breadth of about 420 feet it so ebbs at low water as to leave belts of dry beach, yet affords even then a large extent of floating berth; it experiences a rise in spring tides of 12½ feet, and can bring up to the town at all times vessels of from 200 to 300 tons, and occasionally those of 400 tons. The dues exacted at the port are from 2s. 4d. to 3s. 4d. a voyage of harbour dues; from 1s to 4s a voyage of ballast dues; 2d. per Newcastle chaldron on British ships, and Is. 4d. on foreign ships of export duty on coals; certain dues called plankage and groundage on vessels loading and unloading, and export duties on grindstones, cinders, and salt.

MARKETS AND FAIRS. The meat, vegetable, poultry, and butter market, are held every lawful day in the splendid market buildings formerly noticed. The fish-market is held on the ground-floor of the Exchange on the Sandhill, which place was fitted up for it in 1823, and is well supplied with every variety of fish. The wheat market is held every Tuesday and Saturday, in the large area near St. Nicholas's Church. The cattle and hay markets are held on Tuesday. The former is situated at the south end of West Clayton-street, in front of Marlborough Crescent, and Derwent Place, and the latter in an open area at the head of Percy-street. Fairs for horned cattle, sheep, and hogs; and for cloth, and woollen and other goods, are held on August 12th and the following nine days, and October 29th and the following nine days, and a town fair is held on November 22nd. A fair is held on the last Tuesday in May, and the first Tuesday in every month for the sale of lean cattle. Hirings for farm servants are held in Percy-street, on the first Tuesday 1n May and November. The Newcastle races are held annually in June, on the Town Moor, about a mile north of the town.

COMPANIES, etc. There are in Newcastle twelve companies called mysteries, viz., drapers, mercers, skinners, tailors, merchants of corn or boothmen, bakers, tanners, cordwainers, saddlers, butchers, smiths, and fullers and dyers. There are also, by charter, fifteen companies, called by trades – masters and mariners, weavers, barber surgeons, shipwrights, coopers, house-carpenters, masons, glovers, joiners, millers, curriers, colliers, slaters, glaziers, and cutlers – the last is now extinct. There are likewise nine other companies- merchant adventurers, hostmen, bricklayers, ropemakers, upholsterers, sail-makers, goldsmiths; scriveners, and grocers.

The masters and mariners are better known under their denomination of the Masters and Brethren of the Trinity House. They are a corporate body and are said to have been originally a religious society. They had charters from Henry VIII., Edward VI., Mary, Elizabeth, James I, Charles II, and James II.; and have the sanction, in the matter of licensing pilots, of an act of parliament passed in the 41st year of the reign of George III. Their style and title under their last charter is “The Masters, Pilots, and Seamen of the Trinity House of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, in the county of Newcastle-upon-Tyne.” They are authorised by charter to receive prescribed dues for keeping two lights "the one at the entrance of the haven of the Tyne, and the other on the hill adjoining," and "to appoint pilots, collect primage, and support a number of poor brethren or their wives." Besides the two lights just mentioned, they also have beacons at Holy Island, Blyth, etc., They still exercise all these powers, and appoint and control pilots within the rivers and seas from Holy Island to Whitby. In the year 1505 they erected a residence for their poor brethren, buildings known as the Trinity House, which at present contains a hall, board room, library, school, chapel, and lodgings for the poor brethren. In the school, which is under the superintendence of Mr. Thomas Grey, the children of the poor receive a good education, the course of instruction embracing reading, mathematics etc. The chapel is capable of accommodating 100 persons.

Also in this Directory (Whellan, 1855) for Newcastle:

- Description of Newcastle

- Early history

- Fire of Newcastle & Gateshead (1854)

- Extinct Monastic Edifices

- Fortifications, etc.

- Churches and Chapels

- Public schools

- Hospitals and Almshouses

- Benevolent Societies and Institutions

- Public Civil Buildings, etc.

- Literary and Scientific Societies, etc

- Commerce and Manufacturers, etc.

- Corporation, etc.

- General Charitities of Newcastle-upon-Tyne

- Eminent Men

- Post Office, Newcastle

- Directory of Newcastle-upon-Tyne