Topics > Cumbria > Cumberland (ancient county)

Cumberland (ancient county)

Cumberland was a county of North West England dating from the 12th century. It was an administrative county from 1889 until 1974, when it became part of the new county of Cumbria. See also: the ancient parishes and townships of 'old' Cumberland.

This page relates to the historic county of Cumberland, rather than the 'new' unitary authority area named Cumberland which was formed in April 2023 when local government in Cumbria was reorganised. The 'new' Cumberland unitary authority area includes most of the historic county, with the exception of Penrith and it's surrounding area, which will be in the 'new' Westmorland unitary authority.

Extract from: A Topographical Dictionary of England comprising the several counties, cities, boroughs, corporate and market towns, parishes, and townships..... 7th Edition, by Samuel Lewis, London, 1848.

CUMBERLAND, the extreme north-western county of England, occupying a maritime situation, bounded on the east by Northumberland and Durham; on the south-east by Westmorland and Lancashire, from the former of which it is partly separated by Ulswater and the river Eamont, and from the latter by the river Duddon; on the west by the Irish Sea; and on the north by Scotland, from which it is divided by the Solway Firth and the rivers Sark, Liddell, and Kershope. It extends from 54° 12ft to 55° 10ft (N. Lat.), and from 2° 19ft to 3° 37ft (W. Lon.), and contains 1478 square miles, or 945,920 statute acres: within its limits are 34,574 inhabited houses, 2386 uninhabited, and 200 in the course of erection; and the population amounts to 178,038, of whom 86,292 are males.

This county, in Saxon orthography Cumbra-land, signifying "the land of the Cumbrians," derives its name from having been occupied, after the settlement of the Saxons in Britain, by a remnant of the ancient Britons, styled Cumbri or Cymry. It was also designated Caerleyl-schire, or Caerlielleshire, from its chief town Caerleyl, now Carlisle. At the time of the Roman invasion, it was, according to Whitaker, inhabited by the Volantii or Voluntii, a "people of the forests," and the Sistuntii, both tribes of the Brigantes, whose territory was not subjugated by the Romans until the reign of the Emperor Vespasian. In the division of the island by the victorious Romans, Cumberland was chiefly included in the great province of Maxima Cæsariensis, which was separated from that of Valentia by the fortified wall crossing the northern part of the county. During the heptarchy it formed part of the kingdom of Northumbria, composed of the two smaller states of Bernicia and Deira. About the middle of the tenth century, it was ceded to the Scots, together with the greater part of Bernicia; and from that period it was sometimes under the dominion of their monarchs, and sometimes under that of the English sovereigns, till the year 1237, when it was finally annexed to the crown of England by Henry III.

Its border situation has caused it to be the subject of many remarkable transactions, and the scene of numerous interesting historical events. Even after the Scottish dominion over the northern counties of England had finally ceased, the feuds between the two kingdoms raged with unabated violence for more than three centuries, during which this county was seldom long exempted from the horrors of invasion, or the cruelties and depredations of border warfare. Life and property could only be preserved by a most vigilant system of watch and ward, and the construction of numerous fortresses: almost every gentleman's residence, particularly on the sea-side or near the border, had its fortified tower, sufficiently capacious to afford refuge to the inhabitants of the domain; and in some parishes the church towers were so constructed as to serve for this object. The border service and laws were instituted in the reign of Edward I.; the former for the purpose of keeping a strict watch, establishing beacons, and regulating the musters in time of war; and the latter for the punishment of private rapine and murders committed by individuals of either nation on those of the other in time of peace. A lord warden of the marches, whose authority was partly civil and partly military, was appointed on each side of the borders; the first English lord warden being nominated in 1296. The English borders were divided into three districts, called Marches, namely, the Eastern, Middle, and Western; and Cumberland was included in the last. The wardens held courts, but offenders were frequently executed without trial. The union of the two kingdoms, under James VI. of Scotland and I. of England, having put an end to the devastating inroads and sanguinary retaliations which defile the border annals, that monarch took active measures for ensuring the peace of the harassed district; and to abolish as much as possible the distinction between the kingdoms, he ordered that the counties of England and Scotland which had been called the Borders should be styled the Middle Shires, and thus described them in his proclamation. He soon after banished the Græmes or Grahams, a numerous clan occupying what was called "the debateable ground," near the river Esk, who had long been an annoyance both to their own countrymen and the inhabitants of Cumberland. Notwithstanding these precautionary measures, outrages and robberies continued to be perpetrated for some time after James' accession to the English throne, which caused him to issue several special commissions, under which various beneficial regulations were adopted. All persons, "saving noblemen and gentlemen unsuspected of felony or theft, and not being broken clans," in the counties lately called the Borders, were forbidden to wear any armour, or weapons offensive or defensive, or to keep any horse above the value of 50s., on pain of imprisonment. Slough-dogs, or blood-hounds, for pursuing the offenders through the mosses, sloughs, or bogs, were ordered to be kept at the charge of certain districts; and the laws were enforced against the moss-troopers, as they were called, with the utmost severity: nevertheless, they were not finally extirpated until the reign of Queen Anne.

Cumberland is in the diocese of Carlisle, and province of York, and contains 104 parishes. For purposes of civil jurisdiction it is divided into five wards (a term peculiar to the border counties), respectively denominated Allerdale above Derwent, Allerdale below Derwent, Cumberland, Eskdale, and Leath. It comprises the city and inland port of Carlisle; the ancient borough and market-town of Cockermouth; the sea-port, markettown, and newly-enfranchised borough of Whitehaven; the market and sea-port towns of Maryport, Ravenglass, and Workington; the small but thriving sea-port of Harrington; and the market-towns of Alston-Moor, Aspatria, Bootle, Brampton, Egremont, Hesket-Newmarket, Keswick, Kirk-Oswald, Longtown, Penrith, and Wigton. By the act of the 2nd of William IV., cap. 45, the county sends four representatives to parliament, and for that purpose is divided into two portions, called the Eastern and Western divisions; the former composed of the wards of Cumberland, Eskdale, and Leath; and the latter of those of Allerdale above and below Derwent. Carlisle and Cockermouth each return two members; and Whitehaven, by the act, is invested with the privilege of sending one. Cumberland is included in the Northern circuit: the assizes and the Easter and Midsummer quarter-sessions are held at Carlisle, where stands the common gaol and house of correction; the Epiphany sessions, at Cockermouth; and the Michaelmas sessions, at Penrith.

The surface of the county is beautifully diversified with level plains and swelling eminences, deep sequestered vales and lofty mountains, open heathy commons and irregular inclosures, in some parts richly decorated with tufted groves and thriving plantations, and the whole enlivened with almost innumerable streams and extensive lakes. The mountainous and the level districts form its marked natural divisions. The latter occupy chiefly the northern and western parts, and though well cultivated and fertile, do not afford any interesting scenery, except along the courses of the several rivers. The mountainous lands, between which and the plains there are generally lower ranges of smooth hills, may be divided into two extensive districts, equally incapable of agricultural improvement, but differing considerably in character. The entire eastern and north-eastern sides of the county, bordering on Durham and Northumberland, form the highest part of the mountainous chain that runs through the centre of the island from Staffordshire to Linlithgow, and are chiefly comprised under the designations of Cross Fell, Hartside Fell, Geltsdale Forest, and Spadeadam Waste, amongst which, Cross Fell rises preeminently to the height of 2902 feet, and though steep on its western side, has a very gentle declivity eastward. These mountains, to the south-east, are separated by the level tracts bordering on the rivers Eden, Eamont, Petterill, and Caldew, from those occupying the southern part of the county, which are among the most elevated in Britain, and present a great variety of grand and picturesque forms, their sides being steep and rugged, and in some places ornamented with woods; while the deep vales, mostly rich and in a high state of cultivation, and in many parts well wooded, contain, in numerous instances, lakes of considerable extent; the whole forming some of the most romantic scenery in the kingdom, deservedly eulogized in the descriptive tours of several ingenious writers, and comprehending a pleasing variety of subjects for the pencil.

The most valuable of the minerals are coal and lead; in addition to which, the county produces the singular mineral substance called wad or black-lead, slate, copper, iron, and lapis calaminaris. The coal district is supposed to occupy an extent of about 100 square miles: the principal collieries on the coast are those at Whitehaven and Workington, which supply by far the chief portion of the coal imported into Ireland. The singular species called "cannel coal" is procured in different parts, particularly in the parishes of Caldbeck and Bolton. The most important lead-mines are those at Alston-Moor, which were discovered and worked by Francis, first earl of Derwentwater; and, on the attainder of the third earl, were, together with the manor and his other estates, forfeited to the crown, and appropriated to the endowment of Greenwich Hospital. The ore contains a proportion of silver, averaging from eight to ten oz. per ton: copper-ore has sometimes been found in the same vein with the lead, and this metal was formerly exported from the county in large quantities, being likewise found at Caldbeck, Melmerby, and Hesket. It is also in the lead-mines that the lapis calaminaris is found. Iron-ore of a rich quality is procured in the mines of Whitehaven, and exported to South Wales: there are iron-mines at Crowgarth, in the parish of Cleator, and at Bigrigg, in that of Egremont; and on the sea-shore, near Harrington, ironstone is collected, and a few hundred tons annually sent to Ulverston. The celebrated mine of "wad" at the head of Borrowdale, is described in the account of that place.

The limestone near the sea-coast is burned in great quantities for exportation, particularly at Over-end, near Hensingham, and at Distington, from each of which places about 350,000 bushels are sent every year to Scotland. At Allhallows, Brigham, Cleator, Hodbarrowin-Millom, Ireby, Plumbland, Sebergham, Uldale, &c., are lime-works for inland consumption; and the barony of Gilsland is supplied from the parishes of CastleCarrock, Denton, and Farlam. Gypsum, or alabaster, is more especially abundant in the parishes of Wetheral, St. Cuthbert (Carlisle), and St. Bees, on the sea-coast, about a mile from Whitehaven, whence 500 or 600 tons are annually exported to Dublin, Glasgow, and Liverpool, where it is principally used in the composition of stucco. Of the freestones, which abound and are worked in most parts of the county, there are two quarries producing some of an excellent quality, both red and white, in the neighbourhood of Whitehaven, from which place much of their produce is shipped for Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man. At Negill and Barngill, near the same port, are export quarries of grindstones; and in the townships of Bassenthwaite, Borrowdale, Buttermere, Cockermouth, and Ulpha, are quarries of excellent blue slate: that obtained in Borrowdale is of the best quality. Numerous mineral substances of minor importance, and a great variety of spars and metallic fossils, are found; and divers extraneous fossils, also, are discovered imbedded in the limestone strata in several places.

The Manufactures are various. That of cotton, at present the principal, was first established at Dalston, and soon extended to Carlisle and Penrith, at all which places are large works: the spinning of cotton, which is nearly of equal magnitude, is carried on at Carlisle, and has been the means of greatly increasing the population. At Cleator, Egremont, and Whitehaven, sailcloth is manufactured; and at Keswick, coarse woollen cloths and blankets. Coarse earthenware is made at Dearham and Whitehaven, and bottles at the Ginns, near that town; and there are iron-foundries at Carlisle, Dalston, and Seaton near Workington; paper-mills at Cockermouth, Egremont, and Kirk-Oswald; and several yards for ship-building at Maryport, Whitehaven, and Workington, besides every kind of manufacture necessary for the shipping. The Fisheries, too, are of some importance: there are herring-fisheries at Allonby, Maryport, and Whitehaven, the last on a very extensive scale; and a great quantity of cod is taken on this coast. In the Esk, Eden, and Derwent are valuable salmon-fisheries, the produce of which is sent from Carlisle and Bowness to London, to which place the char caught in the lakes is also forwarded, after being potted at Keswick. The pearls, still occasionally found in the muscles of the Irt, were once highly esteemed.

The two principal Rivers are the Eden and the Derwent, the former of which, after being augmented in different parts of its course by the Eamont, Irthing, Caldew, and Petterill, empties itself into the Solway Firth. In its lower reaches it was made navigable up to Carlisle bridge, to which the tide ascends, a distance of somewhat more than ten miles, under the authority of an act of the 8th of George I.; but the passage was so much impeded by shoals as to form a very imperfect line of navigation, and its use is now almost wholly superseded by the Carlisle Canal, which was constructed under an act obtained in 1819, and, commencing at Carlisle, communicates with the Solway Firth at Fisher's Cross, near Bowness. There are also the Esk, the Liddell, the Levon or Line, and a vast number of smaller streams. The county is furnished with excellent Railway communication. Four lines have their termini at Carlisle; namely, the Newcastle, which runs eastward, by Brampton, and quits the county for Northumberland near the great Roman wall; the Caledonian, which runs northward into Scotland; the Maryport, which runs south-westward, by Wigton, to the coast; and the Lancaster, which proceeds southward, by Penrith, into Westmorland. Other railways connect the coast towns of Maryport, Workington, Whitehaven, and Ravenglass; and there is a line from Workington, inland, to Cockermouth.

The remains of distant ages are numerous and interesting. There is a considerable number even of the rude memorials of the aboriginal inhabitants, the largest and most complete of which is the circle of stones vulgarly called "Long Meg and her Daughters," in the parish of Addingham. About a mile and a half southeast of Keswick is a smaller circle, having an oblong inclosure on the east side; another, named the "Grey Yawd," is in the parish of Cumwhitton, and a third at a place designated Swinside, near Millom, with part of another near it. Kistvaens, and rude weapons and tools of the ancient British inhabitants, have been found in various places, especially in the south-western part of the county, near the sea-coast. Cumberland is thought to have contained several British cities, of which Carlisle is enumerated by Richard of Cirencester as one; and it was formerly crossed by a great trackway, probably of British construction, that extended from the banks of the Eamont through Carlisle, nearly in the line of the present turnpike-road. The "Maiden-way," from KirbyThore to Bewcastle, which seems to have been another British road, may still be traced across the moors in the eastern and north-eastern extremities of the county, in its course into Scotland.

The celebrated Roman wall, constructed by the Emperor Severus, nearly in the line of a vallum of earth previously raised by Adrian, to check the incursions of the northern barbarians, crossed the northern portion of the county, and may yet be traced in different parts of its course, particularly near Burdoswald, Lanercost Priory, and within about a mile of its termination on the shore of the Solway Firth. Of the stations along the line of this barrier, the first that occurs in following its course westward from the border of Northumberland is that at Burdoswald, which, from the numerous inscriptions and other relics, appears to have been the one called in the Notitia Amboglana, occupied by the Cohors Prima Œlia Dacorum, and the remains of which evince its former extent and importance. The next is at Castlesteads, or Cambeck Fort, six miles and a quarter further, which is supposed to have been the Petriana of the Notitia; three miles beyond is Watchcross, conjectured to have been Aballaba. The next was that of Congaveta, at Stanwix, just opposite Carlisle. At Burghon-the-Sands, about four miles and a half further, was the station Axelodunum, on the site of which urns, altars, and inscriptions have frequently been found: at Drumburgh are evident remains of another station, probably Gabrocentum; and the last remains of the wall point to a spot supposed to be the site of the station Tunnocelum, the last on this line of defence. Of the stationes per lineam valli, placed so as to afford support to the garrisons of the stations on the wall, Cumberland contained six, whereof that at Ellenborough, the name of which is doubtful, was one of the most important: on its site the greatest number of Roman antiquities has been found. At Papcastle, near Cockermouth, was another, supposed to have been called Derventio. At Old Carlisle was one more considerable, of which there are extensive remains; as also of that at Old Penrith, or Plumpton-wall, the Voreda of Antonine and Richard of Cirencester: at Moresby was one, thought to have been Arbeia; and the sixth was the station Bremetenracum, the site of which has not been ascertained. There are likewise remains of two advanced stations on the north side of the wall; one at Bewcastle, and the other at Netherby, on the Esk. Carlisle was the Luguballium of the Romans; and, from the great number of military stations, no county in England, except Northumberland, has produced so many Roman altars and inscribed stones as Cumberland, besides a profusion of miscellaneous Roman antiquities.

The principal Roman road across the county, which has been designated "the larger road of Severus," ran nearly parallel with the wall, a little to the south of it; and is yet visible from Willowford across the Irthing to Walbours, a little beyond which place, after being for some distance very conspicuous, all trace of it is lost for some miles until near Watchcross, where it reappears for a short distance. Both the British trackways above-mentioned were subsequently important Roman roads, especially the first, which passed by the stations at Plumpton-wall and Carlisle, and crossed the Roman wall at Stanwix, whence it proceeded by Longtown and Solway Moss into Dumfries-shire: from Longtown a branch diverges north-eastward, towards the station at Netherby, thence to a Roman post at the junction of the Esk and Liddell, and onward to that of Castle-Over, in Dumfries-shire. No fewer than three Roman roads diverged from the station at Ellenborough, one along the coast towards Bowness, another to Papcastle, and the third north-eastward to the station at Old Carlisle, which it passed to the left, proceeding in a direct line towards Carlisle cathedral. A Roman road that connected the stations at Ambleside (in Westmorland) and Plumpton-wall, is still visible in various places, especially near the Whitbarrow camp, which was a post of some consequence between the two Roman towns: at this point terminates a road from the station at Brougham, situated near the town of Penrith, but in the county of Westmorland. Another Roman road, formed of pebbles and freestone, extends from the parish of Egremont through Cleator, Arlochden, and Lamplugh, towards Cockermouth.

Prior to the Reformation, there were eleven Religious Houses, besides two collegiate establishments and two hospitals, within the limits of the county. Of these, there yet remain the churches of the monasteries of St. Bees, Carlisle (now the cathedral), and Lanercost; part of the church of Holme-Cultram; and various ruined buildings of Calder Abbey, the priories of St. Bees, Carlisle, and Wetheral, and the nunnery of Seaton. The remains of Holme-Cultram, and of Lanercost, exhibit specimens of the earliest English architecture, having the pointed arch united with the massive Norman pillar; those of Seaton have lancet-shaped windows and slender pillars. The ancient Castles, owing to the border situation, are remarkably numerous; but most of them are now either in ruins or in a state of considerable dilapidation. Independently of these, few of the ancient mansions present any remarkable feature, except the large square tower of three or four stories attached to most of them, intended to afford refuge for the family on any sudden predatory inroad of the Scots. The most remarkable Mineral water is the sulphureous spring at Gilsland, celebrated for the cure of cutaneous disorders, and long resorted to on account of its valuable properties: besides a considerable portion of sulphur, its waters contain a small quantity of sea-salt, and a slight admixture of earthy particles. There is also a strong sulphureous spring in the township of Biglands, in the parish of Aikton; and a saline spring at Stanger, two miles north of Lorton, nearly resembles the Cheltenham water, turning white on the infusion of spirit of hartshorn, and precipitating particles, chiefly saline, on the application of oil of tartar. There are many other mineral springs, but their properties have not been accurately ascertained. Cumberland gives the title of Duke to the King of Hanover, fifth son of George III., who was created Earl of Armagh, and Duke of Cumberland and Tiviotdale, in the year 1799.

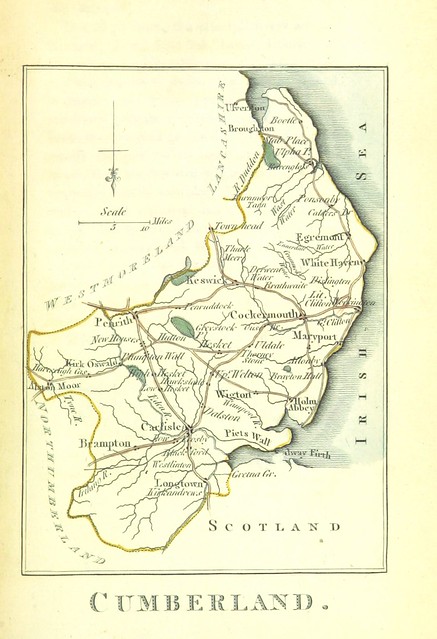

from Flickr (flickr)

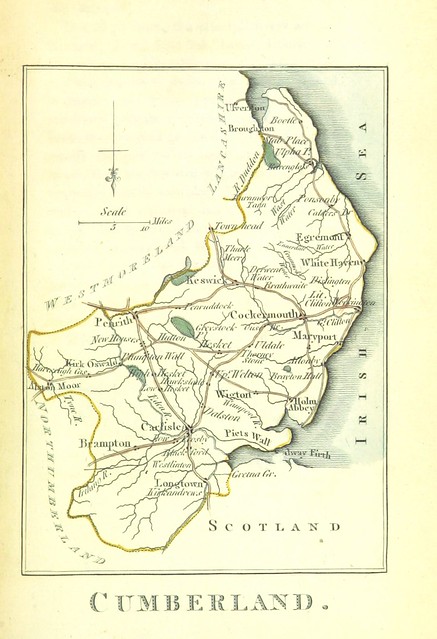

Image taken from page 73 of 'The picture of England. Illustrated with colour'd maps of the several counties'

Pinned by Simon Cotterill

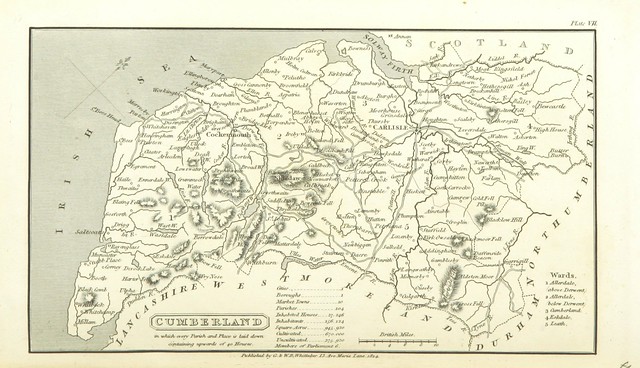

from Flickr (flickr)

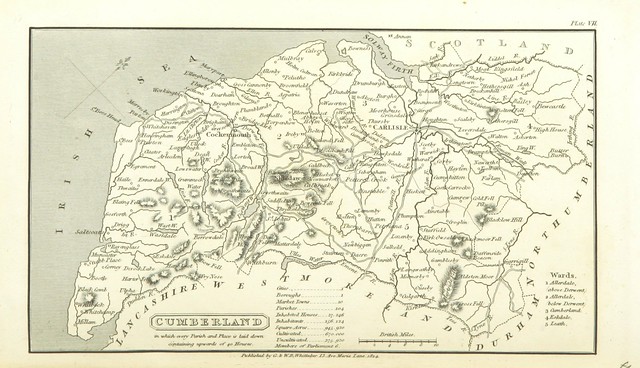

Image taken from page 293 of '[A Topographical Dictionary of the United Kingdom ... accompanied by forty-six maps, etc.]'

Pinned by Simon Cotterill

Co-Curate Page

Westmorland (ancient county)

- Westmorland was an administrative county in north west England from 1889 until 1974, when it became part of the newly formed county of Cumbria. The area of Westmorland now forms …

Co-Curate Page

Three Shires Stone, Wrynose Pass

- Overview Map Street View The Three Shires Stone, at the top of Wrynose Pass near Little Langdale, marks the historic boundary of the old counties of Lancashire, Cumberland and Westmorland. …

from Flickr (flickr)

Image taken from page 73 of 'The picture of England. Illustrated with colour'd maps of the several counties'

Pinned by Simon Cotterill

from Flickr (flickr)

Image taken from page 293 of '[A Topographical Dictionary of the United Kingdom ... accompanied by forty-six maps, etc.]'

Pinned by Simon Cotterill

Co-Curate Page

Westmorland (ancient county)

- Westmorland was an administrative county in north west England from 1889 until 1974, when it became part of the newly formed county of Cumbria. The area of Westmorland now forms …