Topics > County Durham > Easington Colliery - town > Easington Colliery (1899-1993) > Easington Colliery Disaster, 1951

Easington Colliery Disaster, 1951

On the 29th of May 1951 an explosion at Easington Colliery resulted in 83 deaths. An accumulation of flammable gas (firedamp), propagated by coal dust, was ignited by sparks from cutter picks striking pyrites (Source: Durham Mining Museum).

Although the shafts for the colliery had started to be sunk in 1899, the first coals were not drawn until 1910 due to passing through water-bearing strata. Two main pits were sunk: the North Shaft (downcast) and the South Shaft (upcast). Both of these reached down to the Hutton seam, at and respectively. The seams worked were Five Quarter, Seven Quarter, Main Coal, Low Main and the Hutton at the bottom. Underground the colliery was split into a number of distinct areas or districts. The explosion occurred in the West or "Duckbill" district (named after the duckbill excavators used in the district), which lies to the northwest of the shafts and to the north of the village. The village is built over the seams, and to safeguard it from subsidence there is a reserved area under it.

Significantly, one district extends for four miles under the North Sea; ventilation was therefore not simple: enough air was needed to ventilate the extremities of the eastern workings, whilst that for the closer faces did not need such a powerful supply. Too much air in the closer workings would starve the distant ones. Supplementary fans and traps needed to be employed. The Duckbill district was being developed and it appears that the effect of this on the ventilation was overlooked, as admitted by the Assistant Agent (Mr H E Morgan) in cross-examination.

The colliery in 1951

From the pit bottoms the main roadways extended to the north, where the West Level branched off and ran for west to the junction with the Straight North Headings, which head north via drifts into the Five Quarter seam. The West Level continued into a training area. Around along the Straight North Headings was a further junction where the First West Roads headed west. Some distance further on the second and third roads branched off.

Along the First West roads were a number of headings both north and south. The seat of the explosion was at the far end, down the 3rd south heading.

At the end of the 3rd south heading a cross passage was driven and "long wall" excavation commenced on the retreating wall principle. The cutting machine travels from one end of the long wall to the other, and then back. The cuts are made towards the roads, thus the face retreats from the where it started back towards the start of the headings. Behind the cut is a void (known as "goaf") into which spoil was placed and normally the roof is allowed to collapse upon this spoil as props are withdrawn. In the case of the 3rd south workings this collapse did not occur properly and a void developed above the spoil.

Firedamp and coal dust

The area above the goaf was inadequately ventilated and acted as a reservoir for firedamp. The origin of the firedamp is debatable: either the fractured roof allowed a sudden outburst from the seams above, or else the firedamp was gradually emitted from the waste into the void. Roberts discusses these possibilities in the report and comes down in favour of the latter.

All collieries are susceptible to the build up of coal dust, not just at the face but along the roadways and conveyors. Coal dust when dispersed in air forms an explosive mixture. Mines therefore adopt three principal means of combating this risk: removal of the dust, spraying with water and diluting the coal dust with stone dust. All three were practised at Easington, but not in a satisfactory manner.

Firedamp detection

Firedamp detection was by means of a flame safety lamp. Flame safety lamps need to be monitored to be effective, and in consequence the regulations require certain men to have lamps with them. The men are not permitted to also have electric lamps with them, to ensure that they are aware of changes in the flame. However written permission from the mine manager may be obtained to allow electric lamps, and this was routinely given. Since the lamps were not needed for illumination, they become just an additional burden to carry and were sometimes left behind. When the explosion occurred both safety lamps had been left behind at the intake and so were not at the face. Roberts is unsure whether the lamps would have detected the firedamp in time.

Explosion

The coal cutter consists of a rotating part with a number of teeth or picks. When these picks hit a pocket of hard rock such as pyrites or quartz they can generate a finely divided powder which is heated by friction. Blunt picks are more likely to produce this grinding and heating than sharp ones. Sparking from the cutters in the Duckbill district had been observed before, but as nothing had followed from the sparking it was ignored.

At Easington in 1951 blunt picks hit a patch of pyrites and generated sparks. This time the firedamp leaking from the void above the goaf was ignited. The resulting explosion travelled down the south headings to the west roads. Such an explosion in a confined space causes a blast of air which can raise up any dust lying around. Here coal dust was raised and the resulting coal dust explosion now travelled along the west roads, down the straight north headings and into the main coal where it reached as far as the training area. Two falls occurred: one in the main coal shortly before the drifts leading to the straight north roads, the other in the Duckbill district shortly before the 3rd south heading.

Men

At that time Durham mines worked three production shifts and a maintenance shift. The fore-shift was from 03:30 to 11:07, the back-shift from 09:45 to 17:22 and night-shift from 16:00 to 23:37. The maintenance and repair shift was the stone-shift from 22:00 to 05:37. Shift timings related to going underground through to returning to the shaft top, therefore at 04:35 both the stone-shift and the fore-shift were underground at the faces. 38 men from the stone-shift and 43 from the fore-shift were killed, all but one instantly. The man who survived died of his injuries just a few hours later. As a result of the total loss of life in the vicinity there were no eye-witness accounts of the explosion or its immediate aftermath.

At the time of the explosion Frank Leadbitter was just outside the shaft-bottom stables and led some men through the dust cloud towards the disaster. He was joined by William Cook (a fore-overman) who telephoned the colliery manager and arranged for the evacuation of the men. Cook and D. Smith (a head wagon-way man) went along the main coal west haulage road to try to get to the duckbill district. The men continued even after hearing and feeling what they believed was another explosion; a fact marked out for special praise by the Chief Inspector of Mines.

The air was foul with afterdamp. As the rescuers started to move into the affected area the canaries carried were overcome almost at once. The afterdamp led to the deaths of a further two men, bringing the total deaths to 83. John Young Wallace (26) was part of a group travelling along the west materials road when he sat down, fell unconscious and died. All the group were using self-contained breathing apparatus with nose clips and mouthpieces. Wallace's set was tested and found to be satisfactory. Post mortem examination revealed emphysema and it was thought that breathlessness caused him to open his mouth and allow atmospheric air to leak in. The air at that point was thought to contain about 3% carbon monoxide. Three days later another rescuer, H Burdess, collapsed in a similar way and died. The post-mortem revealed bullus emphysema. One bulla (blister) on the left lung had ruptured, leading to pain, a partial collapse of the lung and consequent difficulty breathing. The symptoms were though to have led to the man gasping for breath and thereby drawing in a lethal dose of carbon monoxide.

Visit the page: Easington Colliery for references and further details. You can contribute to this article on Wikipedia.

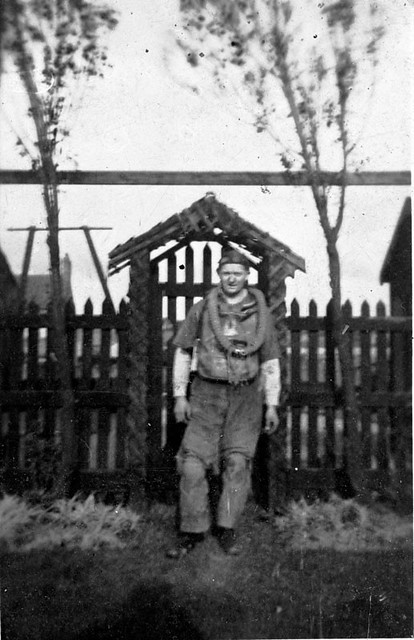

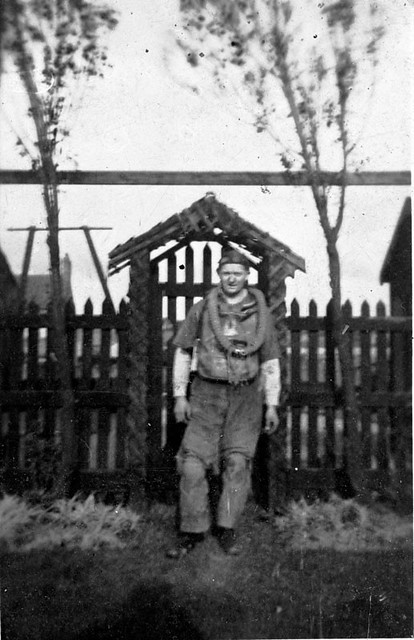

from Beamish (flickr)

Mr Fothergill - Easington Colliery Rescue Team Member

Pinned by Simon Cotterill

from Beamish (flickr)

Easington Colliery Disaster - crowd waiting for news

Pinned by Simon Cotterill

Co-Curate Page

Easington Colliery - town

- Overview About Easington Colliery Map Street View Easington Colliery is a former mining town in County Durham, located close to the coast and ajoining Easington village to the west. The town …

from https://easingtonmemories.wor…

Easington Colliery Memory Book

- "This memory book was created by ED RAW to remember what Easington Colliery was and what it still has the potential to be. Though Easington has undoubtedly been adversely affected …

Added by

Peter Smith

from http://www.thenorthernecho.co…

The miners who never came home

- Northern Echo 23rd Oct 2008. "t was the eerie sound every mining community dreaded. The alarm which signalled an accident underground and summoned miners from their homes to join rescue …

Added by

Peter Smith

from Beamish (flickr)

Mr Fothergill - Easington Colliery Rescue Team Member

Pinned by Simon Cotterill

from Beamish (flickr)

Easington Colliery Disaster - crowd waiting for news

Pinned by Simon Cotterill

Co-Curate Page

Easington Colliery - town

- Overview About Easington Colliery Map Street View Easington Colliery is a former mining town in County Durham, located close to the coast and ajoining Easington village to the west. The town …

from https://easingtonmemories.wor…

Easington Colliery Memory Book

- "This memory book was created by ED RAW to remember what Easington Colliery was and what it still has the potential to be. Though Easington has undoubtedly been adversely affected …

Added by

Peter Smith

from http://www.thenorthernecho.co…

The miners who never came home

- Northern Echo 23rd Oct 2008. "t was the eerie sound every mining community dreaded. The alarm which signalled an accident underground and summoned miners from their homes to join rescue …

Added by

Peter Smith